The OCR championship season is upon us. This brief three-part series takes a look at environmental factors that can affect an athlete’s performance.

First up: heat. Have you ever felt the need to slow your pace early on during a hot race? Read on to discover how your body processes heat, dangers to watch for, and how to inspire adaptation for future performance.

Keeping it [Sub] 100

When exercising in hot conditions, an athlete’s body attempts to maintain a cool 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit via thermoregulation. The human body is heat generation efficient, whereas cooling capacity is limited (Blatteis, 2012; Gordon, 2009). Essentially, your body operates more like a furnace than an air conditioner.

When exercising in hot conditions, an athlete’s body attempts to maintain a cool 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit via thermoregulation. The human body is heat generation efficient, whereas cooling capacity is limited (Blatteis, 2012; Gordon, 2009). Essentially, your body operates more like a furnace than an air conditioner.

Next, consider that heat production is directly proportional to exercise intensity–the harder you work, the hotter you get. So pushing your pace in the heat means you’re climbing an uphill battle, literally and figuratively.

Heat Loss Processes

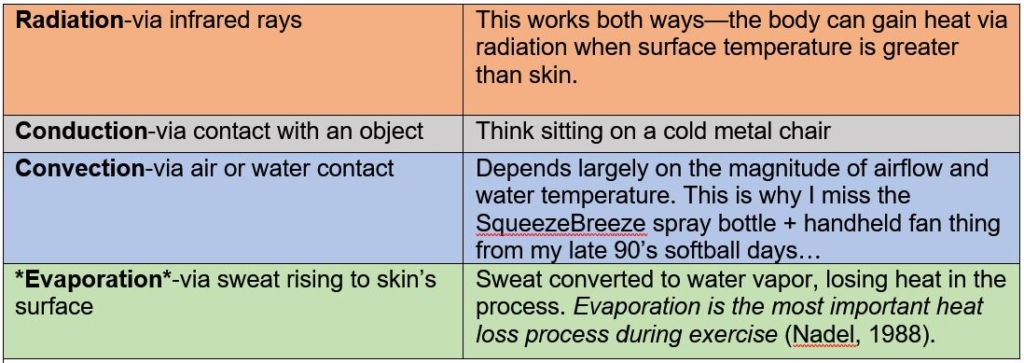

Blood attempts to distribute heat via loss to environment by redirecting blood flow to this skin; this is why your skin feels hotter when you workout. In order for heat to be lost to the environment, a temperature gradient must exist. This means the surface must be cooler outside skin. There are four ways heat is lost from the body:

Evaporation is dependent upon 3 things:

- Ambient conditions—higher humidity, less opportunity for sweat evaporation

- Convective current—see above

- Amount of skin exposed—#ShirtlessforSafety

Remember that when exercise is performed in a hot environment (air temperature is greater than skin temperature), evaporation is the only means of losing body heat.

Performance Impacts

- You’ll “hit the wall” quicker and harder: The rate of muscle glycogen (stored energy in the muscle) degradation is increased with a parallel rise in both carbohydrate metabolism and lactate accumulation. This means you burn more stored energy from the muscle and your body must work harder to process “the burning” in your muscles (hydrogen ions—not the lactate itself—is the cause for the burning, but that is another soapbox rant altogether) (Hargreaves, 2008). Could contribute to muscle fatigue during prolonged exercise in the heat.

- You’ll need to hydrate more and more often: When fluid is lost via sweat, this throws off the cardiovascular function and fluid balance which can lead to dehydration.

- You’ll need to monitor your wellbeing carefully: As your core body temperature rises, heat can affect central nervous system function; hyperthermia, or elevated body temperature, reduces the mental drive for performance. So if you’re feeling down on yourself during a hot race or workout, it can be an indication that your body is struggling with the hot environment.

Don’t Get Burned

Heat-related Injuries

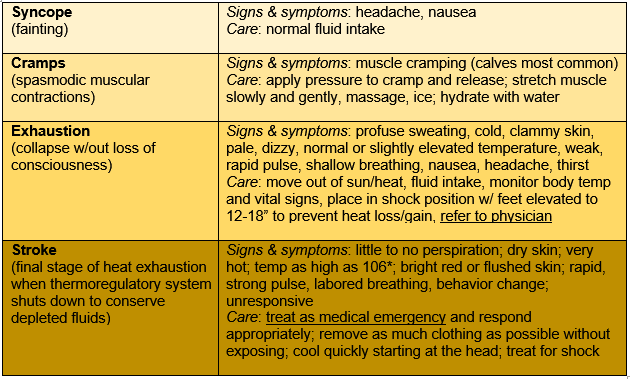

As if I haven’t scared you enough at this point, here are the things you should watch for when exercising in the heat. Disclaimer: I am a Certified Exercise Physiologist, not a doctor, so please consult a medical professional when diagnosing and treating heat-related illness.

(Adapted from Table 24.3 Heat-Related Problems and Their Treatments, McGraw-Hill, 2015)

Acclimation & Acclimatization

Acclimatization is the process in which an individual adjusts to a change in its environment gradually; the aim is to minimize disturbances in homeostasis so that performance may be maintained in said environment. Acclimation is the short-term adjustment to the environment.

Acclimation period: Almost complete acclimation achieved by 7 – 14 days following initial exposure (Brengelmann, 1977; Pandolf, 1998; Wyndham, 1973). Training in a similar environment for a week or two will instigate adaptation essential for race day performance. So training exclusively in a climate-controlled environment prior will not translate well to competition.

Loss of Acclimation: Good news and bad news here. The good news is that acclimatization is not completely lost until 28 days following exposure. The bad news is that there is a significant reduction in acclimation within 7 days removed from exposure. (Armstrong & Maresh, 1991).

Higher, Further, Faster

Adaptation

Exposure to a hot environment leads to the body’s adaptation. Heat acclimation tends to result in a lower heart rate and core temperature during submaximal exercise (Delamarche et al., 1990). Here’s what to expect after adequate exposure in terms of physiology and how that translates to real life:

- Higher sweat volume and earlier onset during exercise = extra laundry is a small price to pay for adaptation

- Reduced amount of salt lost through sweat = maintenance of fluid balance, battling dehydration

- Other things happening to blood plasma volume & with heat shock proteins protecting cells from thermal injury = running in the heat hurts less on a cellular level

Training Tips

It is recommended that an athlete perform strenuous interval training (or continuous exercise > 50% of VO2max) in order to promote a higher core temperature (Pandolf, 1979).

- Consider a HR monitor for your workouts to remain in a target HR zone as HR is sensitive to dehydration, heat stress and acclimation—higher HR means body is working harder

- Stay away from the rubber suits, sauna suits or excessive clothing so that evaporative heat loss is not impended

- Core temperature is lower in morning so heat storage capacity is greater—consider working out in the morning on a hot day

The takeaway here is to be safe when exercising in a hot environment. Take steps to stimulate adaptation gradually, but remember to keep your health in check. I want you to keep racing all season long, and that means in the cold, too! Spoiler: that might be the next installment of The Physiologist Files.

Related reading from MRG Crew battling heat:

The Ultra-OCR Man himself, Evan Perperis, recounts his 48 hours in the pain cave at Endure the Gauntlet.

Fellow science nerd, Wesley Kerr, AKA Dr. Redtights, tackles the Santa Barabara 100.

Very helpful information.