The OCR championship season is upon us. This brief three-part series takes a look at environmental factors that can affect an athlete’s performance. This second entry discusses exercising in a cold environment. Read on to discover how the physiological effects of the cold, dangers to watch for, and how to deal for performance.

The Big Chill

I mentioned in the previous entry that your body operates more like a furnace than an air conditioner. This is good news when exercising in a cold environment, but there are impacts to performance to consider.

Heat Loss Processes

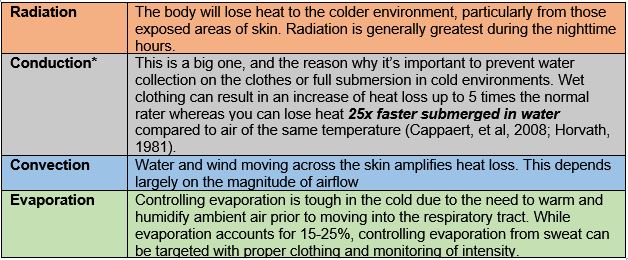

Remember these from the article on heat? Well, they apply in the cold environment, too.

Performance Impacts

- Your body works harder: Rely on carbs more than fat given amped metabolic processes helping to keep your body at homeostasis. This also means higher lactate production which translates to muscular fatigue sooner than expected on a temperate day (Doubt, 1991; Armstrong, 2006; Ninmo, 2004).

- Muscles stay tighter: We all know the importance of a good warm-up, right? Continual movement to inspire blood flow and heat distribution is required. Failure to do so means a cooling of skeletal muscle temperature which hinders performance. It also reduces power and flexibility!

- Dehydration is real: You’re still losing water via sweat and breath, even if it is not as obvious in the cold. Further, the normal thirst mechanism can be blunted with cold exposure (Cappaert, et al, 2008).

Stay Toasty

Heat Retention Processes

This is how your body responds to maintain that toasty 98.6°F.

- Increased thermogenesis

- Nonshivering: increased metabolic heat production (other than muscle contraction)—this means your cells are working harder to produce the heat required to maintain a normal body temperature

- Shivering: involuntary muscle contraction for the purpose of heat production

- Peripheral vasoconstriction: blood vessels limit the amount of blood (which carries heat) flowing to the extremities

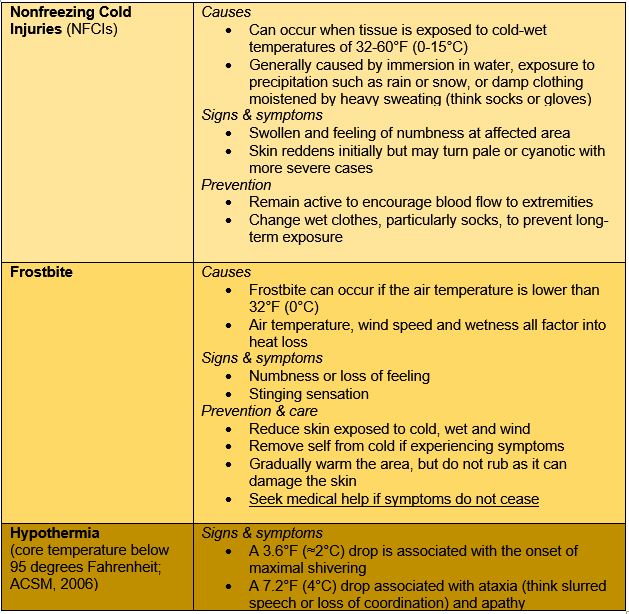

Cold-related Injuries

Characteristics such as clothing, age, body fat percentage, hypoglycemia, precipitation and wind all contribute to potential injuries when exercising in a cold environment (ACSM, 2018). Disclaimer: I am a certified Exercise Physiologist—not a doctor—so please consult a medical professional when diagnosing and treating a cold-related illness.

Acclimatization & Acclimation

Acclimatization is the process in which an individual adjusts to a change in his environment gradually; the aim is to minimize disturbances in homeostasis so that performance may be maintained in said environment. Acclimation is more of a short-term adjustment.

Acclimation period: Unfortunately, research suggests that your body is slower acclimate to the cold, and it is tough to pinpoint exactly when acclimation occurs. Overall, repeated exposure to mild cold rather than severe cold (such as water immersions) seem to lead to adaptations by way of increasing nonshivering thermogenesis (Daanen and Lichtenbelt, 2016).

Not Entirely Hopeless but Why I am Moving to the Equator

Adaptation

Continued exposure by habitation in a cold environment more thoroughly assists in the body’s adaptation. Essentially, you might feel less pain or discomfort after a week of exposure, but you are probably best to prepare with your layered clothing for a race. If you do spend enough time in the cold, here is what to expect after adequate exposure in terms of physiology and how that translates to real life:

- Reduction of the temperature when shivering begins—start shivering at a lower skin temperature.

- Less shivering necessary due to increased nonshivering thermogenesis or metabolic heat production (Cabanac, 1975; Hong et al., 1987)—turning up the body’s furnace.

- Cold acclimation tends to result in improved intermittent peripheral vasodilation to increase blood flow (and heat flow) to both the hands and feet (Makinen 2007, 2010)—good news when it comes to runs and rigs!

Training Tips

Overall, training in the cold is one part safety, one part mental fortitude. Keeping in mind the dangers while preparing adequately for exposure is key. If you are looking to tackle training in the cold keep these in mind:

- Remember that evaporation of sweat happens at much faster rates due to lower water vapor pressure gradient, which cools the body quicker than a warm environment. You may not even realize that you are sweating, which results in insensible water loss. Take a water bottle with you as a reminder to keep hydrated.

- Get to know your footwear. If you are wearing a shoe that prevents evaporation of sweat, consider packing an extra pair of socks in your bucket for longer training events.

- Layer effectively! Consider three layers:

- Inner layer-lightweight polyester

- Middle layer-primary insulator (think fleece or wool)

- Outer layer-designed to transfer moister from the body while protecting against wind and rain (maybe skip this layer in dry and still conditions)

- Reduce insulation as exercise intensity increases.

- Masters competitors—know that individuals older than 60 are less tolerant overall and should be extra cautious.

As with the heat, the takeaway here is to be safe when exercising in a cold environment, especially when combined with rain, snow and/or wind. Prepare smart this offseason, folks! Stay tuned for the final installment of The Physiologist Files where I will discuss the effects of altitude!

Further reading:

Wesley Kerr, AKA Dr. Redtights recounts his battles with the cold at WTM and digs deeper into the science with the Hypothermia Paradox.

Leave A Comment