Perspective on Traumatic Injury

Long ago when I was a much younger man, in 1994, I did something very stupid. Although I was a very experienced gym rat, I did a lift at work that changed my life. It was only 25 pounds multiplied by about 20 reps. I lifted reels of wire from one pallet, twisted, and put them down on another pallet. It was the classic lift bending at the waist and twisting with the feet firmly planted. The trauma resulted in a classic herniated L5 disc. For the next few months, I fought pain and paralysis. Even today, the top of my left foot is numb from the nerve damage. Turns out that nerve damage also put my quadriceps to sleep to some degree. I had lost some strength and did not even know it.

A herniated L5 putting pressure on the spinal cord

But the real story, and the root cause of this apparently sudden injury, started years before. Like many teens and young men, I carried a fat wallet in my back pocket. Not a problem while standing. But when sitting for hours a day behind the wheel and at university classes, that little one-inch bulge offset my lumbar vertebrae, slowly and surely creating more and more weakness and stress over the years.

As a father of a little toddler, I was petrified that I might not be able to pick up my little boy, to love him, play with him, and bounce him on my knee. So I worked hard to come back strong by faithfully following all my rehab workouts. The problem is, none of that worked. What finally brought relief was the third and final round of spinal epidural shots.

Living with Post-Traumatic Injury

From then on, I have had to be extremely careful about my physical activity, mostly by avoiding more stupid moves like lifting and twisting. Then in 2012, I discovered a new way to aggravate that pre-existing condition: OCR.

The move that got me was a team phone pole carry while running. That massive weight plus running equaled a series of compressions on my lower spine. Once again, the shooting pain from my hip to my toes sidelined me for about three months. To stay in the game I simply shifted my workouts to the upper body.

I share all of this introduction with you to drive home two points: First, cumulative micro-trauma is often the root cause of what appears to be a sudden debilitating injury. These little things, usually due to imbalance, asymmetric movements, poor body mechanics, and bad technique, silently add up over time if not corrected by a knowledgeable coach. Second, once that massive injury happens, you never really get over it. The damage is done. No matter how much you correct the micro-trauma, you can only prevent further damage.

Maybe.

How Micro-Trauma Builds Up Over Time

Here's what happened to our very own Bonnie Wilson here at Mud Run Guide:

My training fell out of balance and I didn’t spend enough time on strength, stability and mobility. I paid for it pacing the half marathon before Valentine’s Day. I had just been doing treadmill and stairclimber for a couple months and I didn’t realize how much damage I was doing with that repetitive action. I am on a new plan that is more balanced. But I pulled out of two races to focus on that.

You see, the body is a sneaky thing and it does stuff without telling you sometimes. Or perhaps the warning signals were there but ignored. I saw my chiropractor a number of times to help me with some pain I experienced while running. It always presented in my left leg. Ultimately he diagnosed the fact that my right glute was not firing – at all. That made my left glute and leg take on a disproportionate amount of the work when running. So he gave me some exercises to teach my glute to fire again, build strength, and correct the asymmetry.

That glute issue had likely been building since the day I herniated my L5 in 1994. Twenty years later, that cumulative micro-trauma, in the form of L5 nerve damage causing muscular weakness in my glute, resulted in a whole new series of troubles.

If the glute does not work well, then that weakness simply cascades down the leg, leaving the quads weakened. When the quadriceps are weak, the protective musculature around the knee is compromised. When this happens, the knee is set up for injury.

December 2015 – I was training the dreaded bucket carry. The five-gallon bucket was loaded with sand somewhere between 50 and 70 pounds. After Palmerton 2015, when they put the sandbag carry up into the rocks and boulders single track, I decided some simulated heavy carry like that would be good. I stepped up slowly onto a tire with my left foot. I pushed off with my right to get up. The right knee gave out. It didn’t hurt, didn’t swell, and felt pretty good in fact. But I didn’t want to chance anything by trying that move again. That kind of thing had never happened to me before. So I took what I thought was the road of caution by backing off and swearing never to do that again. It could wait until Palmerton 2016.

March 2016 – I was doing some ninja training at a local gym. I jumped up onto a high box, swung my right leg over and planted that foot on the ground. Coming down, my left leg hung up on the top of the box. My body was already in motion to dismount. The perfect storm was set for a high load stress against a fixed point of my body. The right knee was the only thing that could pivot. Funny thing about knees is they are not designed to do that. The quadriceps are there to provide the strength and flexibility to the knee in order to protect it from the normal daily impacts.

A trip to the MRI revealed that I had indeed torn my ACL. Surgery was required to fix it. I was out for at least a year starting September 6, 2016. At the diagnosis, my orthopedic surgeon told me that I had also torn my meniscus. Usually, that’s the way it happens. An athlete tears the meniscus first. This sets up a stress riser, a cumulative trauma, a weakness, that paves the way for a torn ACL. But this was just the breaking point from a long list of my cumulative traumas reaching back 45 years.

Terrain Race NJ – my final fling before surgery

Sure enough, it was the end of my OCR season and training and everything I knew and enjoyed about this sport. I was devastated.

Emotional and Mental Victory over Traumatic Injury

Around the same time, one of the elite OCR athletes who we all know and follow, Amelia Boone, also suffered a season-ending injury. She fractured her femur. While my injury was devastating, Amelia’s was life-altering. As an OCR pro, her career was at risk. Sure, she could fall back to being a full-time corporate lawyer, but to just stop OCR cold and never come back was unthinkable. As she crutched around from race to race, trying to keep up appearances from the sideline, she started to think, and she started to write. I closely followed her every word.

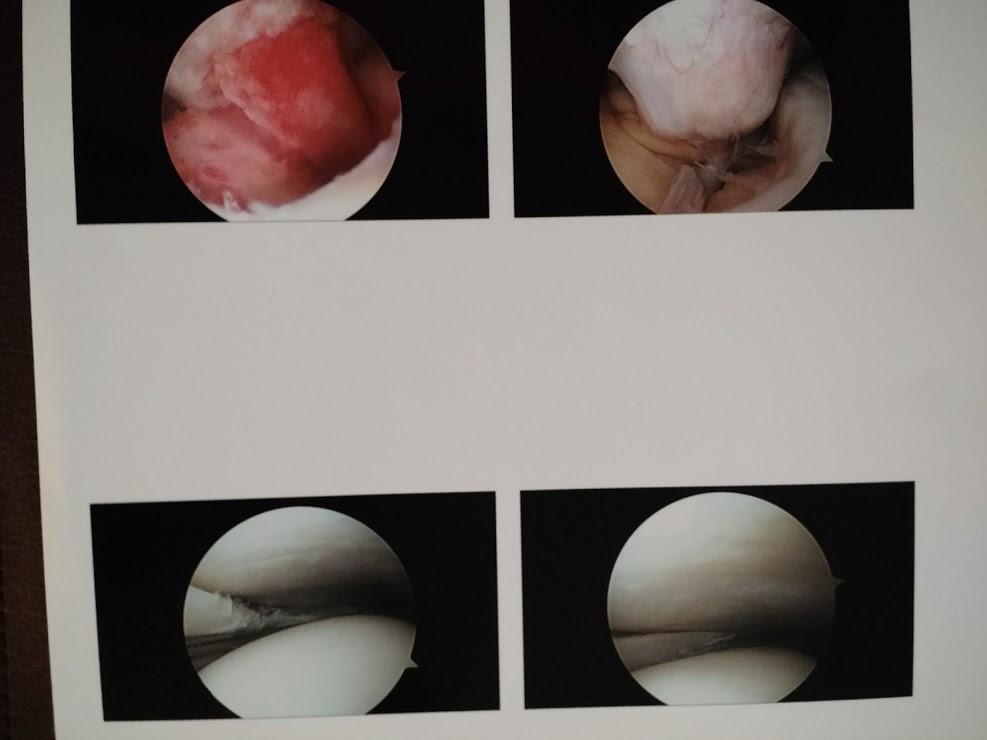

Out with the old ACL/Meniscus – in with the new

Her journey became my journey. As she emerged from her pain, frustration, and feelings, so did I. We exchanged a few comments here and there. From me, it was just small thanks for being so open, how it helped me, and glad expressions for both of our recoveries.

We both stayed in the game by training what we could, attending races to encourage our friends, and writing about our experiences. I think we both realized how therapeutic writing can be when we are transparent. Getting sidelined by a major injury for some extended period of time sucks. I was out for a year minimum. The 2017 season was the worst of my life. But on the other hand, I learned so much about toughness, inner peace, and persistence from a person whom I have never met.

The Physical Comeback

My physical comeback started the day after surgery. The anesthesiologist taught me all about putting the quad to sleep just as he administered the nerve block just before knocking me out. He said it was like a concussion. The quad became 100% non-functional. The nerve block for ACL surgery provided not just pain relief, but also removed the muscle actions upon the knee. This enabled the surgeon to work on replacing the ACL without any muscle stress. Unfortunately, the nerve block does its job so well that upon waking up, the quadriceps were utterly useless. They became target number one for physical therapy starting the next day.

The ice machine – six weeks of rehab

After surgery, the quadriceps are the main focus of the physical therapist and you for the next month or so. On days one through N post-op, all you are doing is following the clinical treatment protocol to learn how to make your quads work again. Right now you can flex your quads without even thinking about it. Now imagine thinking as hard as you can, squeezing with all your might, and those quads don’t even quiver a millimeter. Not even a twitch. They are down hard. And you are nothing but determined to make them work again.

One week post-op

When we train and race, that determination works just as hard to make those quads fire for all they’re worth. Most of the time they do their job wonderfully. They provide the strength and protection we need. Here’s the problem.

If the quads are weak, they allow micro-trauma to the ligaments. Once a ligament in a closed joint like the knee tears, it never heals. There’s very little blood flow inside, very little fluid. No blood means the body can’t send the healing elements needed. You see this process all the time on your skin. You get a cut. It bleeds. The capillary-rich subdermal skin sends the oxygen, white blood cells, and other healing fluids to the wound site. You get a scab. Eventually, that goes away and you’re left with a sore spot for a while. Then it all clears up and it’s like nothing ever happened.

All suited up and race ready for 2018

That’s not how it goes with the meniscus and the ligaments of the knee. They never heal. They may feel better from time to time as you apply a variety of treatments. PRP, prozone, steroids, and other medicines can all help reduce inflammation. These may help the pain go away. But they don’t have any effect on the micro-traumatic tears. That’s why athletes can go a long time with such injuries, fooling themselves into thinking that since there is no pain, there is no injury. All they are doing is prolonging the inevitable.

At this point, the weakness of the quad in synergy with the micro-trauma tears in the ligaments grow progressively worse. The weaker the muscle, the less support it gives to the ligaments. The less support, the more vulnerable the ligaments become to micro-trauma. The more micro-trauma, the more pain and tears and ultimately, complete failure.

Is there a number, a point of no return, a time when you just know you better stop and get this thing looked at? No. Nobody can tell you that. Usually, we all wait until it is too late. Then it’s off to surgery, the nerve block, 100% muscle failure, and the long road to teaching that muscle to fire again. Now you have to reverse the whole process by building the muscle back so that it protects the repaired or replaced ligaments. After all, you certainly don’t want to go through this experience again.

Not All Micro-Trauma is Bad

These are some other nuggets of wisdom I have learned and used over the years.

Don't ignore chronic pain. Chronic pain is pain that does not go away. Pain that only shows up when you do a particular move is not necessarily chronic pain. It's sometimes very difficult to tell the difference. As an athlete, you know your body better than anyone else. Therefore, you should be your own best first line of defense when it comes to the treatment of pain. Do this by eliminating the variables. In this case, determine if the pain is chronic or not. Chronic means it's time to see a doctor. Periodic means you might be able to fix it yourself with proper recovery, proper mechanics, and other tools at your disposal. One of my favorites is The Knee Pain Bible by Christopher Kidawski. The author does a fantastic job of helping you with self-diagnosis of knee pain, treatment, and recovery. As he says, read this before you get surgery.

As athletes, we tend to focus on pain in the subconscious realm. Our training and racing produce the desirable effects of faster times, stronger climbs, and longer endurance. We don’t think about the micro-traumas until one of them starts to hurt.

That’s when rationalization kicks in. We tell ourselves all kinds of stories to keep going through the pain. Sometimes this is wise and effective. Other times, there’s just no substitute for an MRI. This is especially true when a shoulder, elbow, knee, or ankle joint is involved. It is critical when the spine is a candidate.

So you better believe that I do a lot of leg work now. Looking back, such workouts were neglected. I figured I didn’t need much beyond just running and climbing and jumping around. That may be fine for daily life, but OCR requires a much higher level of protection. Leg day is mandatory. Yes, we love to joke about it, skip it, maybe hold back on it, but we do this at our peril. Do leg day. Protect those knees. That’s what the best coaches in the OCR business will tell you – Diaz, Culp, Welch. While their promo may be on the outcome to make us better runners, the realities exist in the development of strength.

Humans of any age are not invincible no matter how much cool stuff they can do on the course or gym. So when trauma happens, pay attention to it. Purposefully look for and eliminate sources of imbalance and asymmetry in the way you sit, stand, and move. Add stabilizer workouts to your WODs that focus on the shoulders, hips, knees, and core. Recognize that not all pain, even chronic, requires surgery. Don’t ignore your heart. It’s a muscle that also requires proper exercise. Heal your mind from past pain and trauma so you can move on unhindered. Failure to do so can induce physical and chemical memory reactions that create the same imbalance and asymmetry that led to trauma in the first place.

First trail run post-surgery

What a journey!! Thank you for the awesome info.

Thank you Melissa. You’ll be glad to know I’m back to 100% and competing this season. See you on the course.